Friday June 19, 2020

TROY R. BENNETT

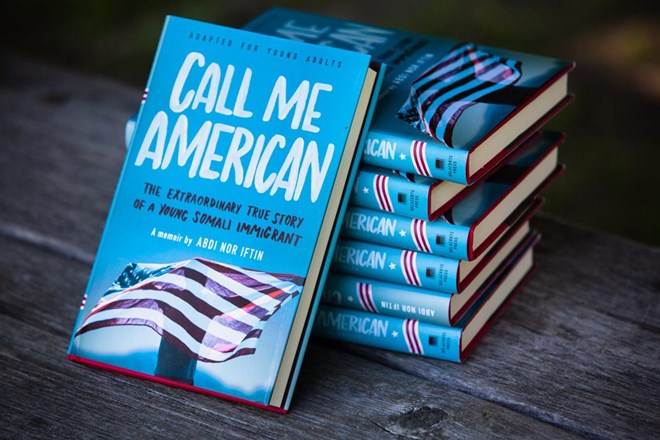

Somali-American author Abdi Nor Iftin published a young adult version of his acclaimed personal memoir this week. Iftin hopes to reach a younger audience with his book and help explain why black lives matter. Credit: Troy R. Bennett / BDN

YARMOUTH, Maine — Abdi Iftin believes in the power of storytelling and thinks it can help bring a racially divided America together.

In 2018 he published his memoir, telling the harrowing story of surviving a malnourished childhood in Somalia, fleeing terrorists who wanted to kill him and his years trapped in a Kenyan refugee camp. It also recounted his winning a U.S. visa lottery before finally making his way to a new home in Maine.

This week, Iftin published a young adult version of his book “Call Me American.” It’s a toned-down adaptation of his story more suitable for children. He wants to get it into schools and in front of young Maine readers. Iftin hopes his tale can humanize the immigrant, and African-American, experience for a young, white audience.

As continuing protests across the country in the wake of George Floyd’s killing highlight racial injustices, Iftin wants to help explain why black lives really do matter.“There are wonderful agencies in Portland and Lewiston who help immigrants who are struggling,” Iftin said. “But my job is to talk to the other side, to tell my story.”

He’s been to Black Lives Matter events in Brunswick, Portland and Yarmouth, but Iftin believes that personal stories are a better way to bridge the understanding gap between black and white, especially in a state such as Maine that is more than 95 percent white. He wants to capitalize on the national media attention his first book garnered and use his elevated voice to start making one-to-one connections with young people in their schools.

“We need white people with us,” Iftin said, “and I don’t want to want to divide America into black and white. That’s horrible.”

The new book, aimed at middle-schoolers, doesn’t leave out any major plot points from the adult version. It just softens some of the more disturbing details. It’s also shorter.

“The [original] book has a lot of traumatizing events from my life that are not really appropriate for anyone under 16 — where I dive deep into my life as a civil war child — the hunger, the drought, the death and destruction,” Iftin said. “I describe burying my own sister when I was 7 years old.”

Since publishing the first book, he’s given many lectures and book talks where children were in attendance. Iftin said he tried to remember their questions when writing. He wanted to address their concerns directly.

For example, he said young people are always surprised to hear that he was born out in the open, under a tree and doesn’t know his exact birthday. He believes it was sometime in 1985, making him now around 35-years-old. Birthdays just weren’t important where he came from. There were no parties, no cake, no presents.

“Living and breathing were priorities, first,” Iftin said. “I grew up surviving.”

He wants his YA readers to understand their privileged, white American experiences are not universal. Iftin wants them to reconsider what they take for granted.

Abdi Nor Iftin’s memoir “Call Me American” was released in a new, young adult version this week. Iftin said he believes in the power of storytelling as a way to bring Americans together. Credit: Troy R. Bennett | BDN

Iftin, now a U.S. citizen, has a complicated relationship with his new home country. For years, Iftin was focused solely on getting to the United States. America was his only dream and its racism never crossed his mind.

Iftin said he didn’t know black until he came here.

“In Africa, my skin color is not visible,” he said.

But Iftin landed at Logan Airport in Boston on the very day in 2014 that police shot and killed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. He saw the angry protests on television and heard the phrase “Black Lives Matter” for the first time. He began to understand the concept of racism, even feeling it in his new home in Yarmouth.

“I went to introduce myself to the neighbors because I was the only dark-skinned guy on the whole, five-mile road,” Iftin said. “If I was a white guy, adopted by this family, I would not have had to do that.”

Iftin said he’s never had a bad interaction with police in Maine but he’s always careful to drive under the speed limit and keeps his hands out of his pockets when he’s in stores. Police incidents with black men in other states that have ended in shootings and death are never far from his mind.

“And I disagree that there’s no racism in this state,” Iftin said. “If you drive from Lewiston, through Turner and all the way to the Rangely area, you see nothing but Trump signs.”

He equates the president with anti-immigrant, racist policies such as family separation at the southern border, children in cages, Muslim travel bans and equivocation about far-right extremist marchers in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Still, Iftin believes in his American Dream and that things can get better.

“I’m frustrated but I will not give up on America,” he said. “I’m not moving anywhere else and I will fight for it.”

“This is home and I have a voice. I don’t want to run away from this opportunity,” Iftin said.

With libraries and bookstores mostly shuttered by the coronavirus pandemic, Iftin hasn’t yet had much of a chance to tout his new book. He says he’s gotten inquiries from several schools, though, and hopes to visit them when they reopen in the fall.

In the meantime, he’s working with a production company on a multi-part documentary project that will tell his story to a viewing audience. He’s also receiving messages from other immigrants with personal stories to tell. Iftin would like to help them do that, to make their own voices heard, to make their own connections with their neighbors.

“I think the best way we can fight racism in this country is to empower the next generation to tell their stories,” he said. “That’s what empower really means — it means telling the truth.”