Sunday October 8, 2017

Abdikadir Negeye, who is from Somalia, is assistant director and human resources director of Maine Immigrant and Refugee Services in Lewiston. He spent 15 years in refugee camps before coming to America. Staff photo by Ben McCanna

LEWISTON — The Kenyan refugee camp where Abdikadir Negeye grew up didn’t have a manicured soccer field. Their ball was clothing scraps wrapped in plastic. Everyone played barefoot.

But Negeye and the other Somali children in the camp played constantly.

“Soccer is everything,” said Negeye, who is now 32.

Negeye, who still keeps the laminated badge that identified his soccer team at the refugee camp, is now one of about 6,000 immigrants born in Somalia and other African countries and living in Maine, according to the U.S. Census.

Somalia, because of a decades-long civil war and famine and drought, has been the largest single source of refugees arriving in Maine during the past 15 years. A total of 1,621 Somali refugees have been resettled in Maine since 2002, a number that does not include family members who followed them or so-called secondary refugees who moved to Maine after arriving elsewhere in the U.S.

Negeye has lived in Lewiston since 2006. But he has no memories of his home country because he was just 6 years old when his family fled their village in 1991.

He spent his childhood in the sprawling Dadaab camp in Kenya, where he lived among more than 240,000 refugees and asylum seekers.

Negeye’s family belongs to a minority ethnic group, Somali Bantus, who became targets during a civil war that began in early 1991. His parents had relatives who were killed, and so wanted safety for their children. Negeye’s mother and father carried him on their backs as the family walked more than 300 miles from their village in Somalia to the United Nations refugee camp in neighboring Kenya. A younger sibling died after the monthslong journey to the refugee camp.

“There’s a lot of people who have lost their lives on the way to refugee camps,” Negeye said. “Those who are lucky enough have made it to the refugee camps. Some people are killed by animals. There are some people who died for hunger or lack of water or medical complications.”

In the camp, his family lived in a hut with a single room. They collected rations of maize from the United Nations, but sometimes it was only enough for one meal a day for Negeye and his five siblings. Medical care was lacking. Negeye went to school, where he remembered his fellow students were not organized by age or divided into grades.

His favorite subject was English.

“Sometimes we were learning something with our stomachs empty,” Negeye said. “Sometimes we were walking to school without shoes. But I still had that hunger there for education.”

Refugee status is a designation given by the U.N. to people who have fled their countries because of persecution, war or violence. Less than one percent of 14.4 million refugees are permanently resettled in another country, according to the U.N. Refugee Agency. But the conditions in their country of origin made it impossible for the Somali Bantus to return there, and in 2000, the U.S. government agreed to accept 12,000 refugees from that group.

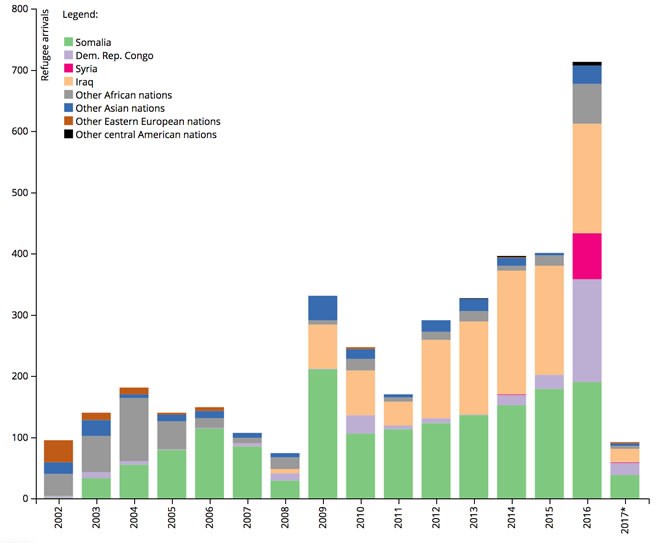

Maine refugee arrivals, by year and by nation of origin:

Refugees are brought to the United States to escape violence or persecution. Here is a look at the number of individuals resettled in Maine each year, and where they were born. It does not include refugees who moved here after first resettling in other states. Note: 2017 data are current as of Aug. 31.

For the next five years, while still living in the camp, Negeye and his family were interviewed repeatedly by U.S. immigration officials. They were required to pass medical examinations and security checks. They moved to a new refugee camp in order to complete additional screenings and interviews. In total, Negeye lived in the camps for 14 years.

“All those long waits, sometimes to be honest, I even felt I will never come to America,” Negeye said.

In January 2006, the wait ended.

The family landed in Atlanta, Georgia. They brought a small amount of clothing and a few personal items, including Negeye’s soccer badge. The traffic lights and the highways of the large southern city overwhelmed them immediately. Negeye remembers his frustration trying to understand people with Southern accents as he tried to place a money order with his limited English. Their relatives and friends from the refugee camps had been resettled in other states, including Maine. They felt alone in their new country, so they moved to Lewiston in April 2006.

“It’s a smaller city, less crime and less crowded,” Negeye said.

Negeye was eager to get an education. He enrolled at Loring Jobs Corps in Limestone and earned his high school diploma there in 2007. Then he earned an associate degree at Central Maine Community College in 2011 and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Southern Maine in 2014.

He worked full time while in school. His family received government assistance when they first arrived, but Negeye said they wanted to work as soon as possible. One of his first jobs in Maine was with his father at L.L. Bean in Freeport in 2007. Negeye got a job as a language facilitator in the Lewiston School Department in 2009 and stayed there until 2014. His dad now works at a doughnut shop, and his mom works in childcare.

“Today, my family, they are all taxpayers,” Negeye said. “They are contributing to the community. That is something we all wanted to do. I know the language was still an issue, but there’s a lot of things they could do. The language barrier, it didn’t stop them.”

In Lewiston, Negeye and some friends began talking about a need for academic tutoring and after-school activities for young immigrants. Among them was Negeye’s friend Rilwan Osman. Their families had been friends in the refugee camps in Somalia. Osman had advised Negeye to come to quieter Lewiston when he felt overwhelmed in bustling Atlanta. In Maine, they shared a concern about refugee children who were struggling with the language barrier and failing to graduate high school.

“We asked ourselves, if nobody is going to come help our kids, we need to do something,” Osman said.

In 2009, they started the Somali Bantu Youth Association of Maine with just a van and some athletic equipment. They ran a youth soccer program for 50 kids that first summer.

Negeye wanted to pass on the lessons soccer taught him in the refugee camp.

“Being responsible, being respectful of each other, being punctual in everything, teamwork,” he said.

In 2011, Negeye applied for naturalization and took his citizenship test. When he passed, he came to school to find his students waving American flags in the hallway for him.

“People will still question about me being a citizen,” he said. “Today I have a lot of responsibilities as a U.S. citizen, and I take the oath to defend this country and to die for it. My kids are all born here, and this is where I call home.”

His volunteer work grew more demanding. Negeye and his colleagues at the Somali Bantu Youth Association saw a need for adult classes in English and financial literacy. Many refugees also need counseling to address post-traumatic stress disorder. They decided to expand their services. In 2014, Negeye left his job at the Lewiston schools and took the role of assistant director and human resources director for what would be renamed Maine Immigrant and Refugee Services.

“We saw the need in the community,” said Osman, who had also previously worked for the Lewiston schools. “We saw how not only the youth but also the parents were struggling when it comes to adapting to the new culture.”

The nonprofit now employs more than 50 people. The summer soccer program hosted 250 players this year. The entry to Negeye’s office is papered with newspaper clippings about the 2015 Lewiston High School boys’ soccer team, which won the state championship and included eight Somali players who grew up in refugee camps.

“I want to give back to the community that has invested in me, educated me and made me who I am today,” Negeye said. “People, if they say, do you want to move? I always say no. This is where I call home, and I’m not going anywhere.”

He met his wife, who is also a Somali refugee, at a wedding. Their four children are still small – the oldest is just 8 years old – but Negeye hopes they play soccer someday. He will be able to take them to a real soccer field, where they can run in cleats and pass a real ball to each other.

“The first thing you will see them start kicking will be a ball,” he said.