Hawa Hassan was 7 when she flew to Seattle from Somalia to be resettled along with a group of refugees after spending three years in Kenya. Her mother and siblings were expected to join her soon after, and all she remembers about her arrival in her new city was snow.

Hassan didn’t know it at the time, but it would be 15 years before she saw her family again. Her mother and siblings encountered visa issues and ended up settling in Norway.

In the interim, the skinny, awkward girl who found herself alone in Seattle made the best of the hand she’d been dealt. Hassan capitalized on every opportunity she was afforded, and now, more than two decades after she first arrived in the U.S., the model-turned-food-industry-rising-star is the founder of Basbaas Somali Foods, a successful condiment company that specializes in Somali hot sauces and chutneys. She released her first cookbook, “In Bibi’s Kitchen,” last fall, and has a second cookbook in the works — this one explores civil war and food “from the lens of others,” Hassan says, and examines what happens with food when a country fights within its own borders.

The road to CEO and cookbook author hasn’t always been easy, but “I have no sad stories to tell,” Hassan says. “And it’s not because I have none. I have sadness in my life, but I have blessings.”

Hawa Hassan fine-tuned the recipes for her Basbaas condiment line while staying with her childhood best friend in Seattle. (Courtesy of Hawa Hassan / )

Count your blessingsLooking back, Hassan, now 35 and living in New York City, sees the time she spent in Seattle as a formative period in her life.

But in the first few years after her departure from Kenya (a year of which was spent in a refugee camp), Hassan didn’t register much about life in Seattle other than the fact that “my family isn’t here, but I have a job to do.” To get herself up, dressed and ready for school. To walk to the bus stop. To clean up after herself.

As a little girl growing up in Seattle’s South End, thousands of miles away from her family and homeland, Hassan recalls sometimes struggling to fit in amid her new surroundings.

“In the ’90s, I think it was an especially difficult time to be a Black American,” Hassan says. “But it was also a time where they were especially aware of Africans … if you were an African kid thrown into this new society, you were the butt of all jokes.”

She wore a hijab for “quite some time” and says there was a “small moment” where she didn’t want to be Hawa, instead asking people to address her by her middle name “Ali” — because it sounded closer to the Americanized, Anglicized name “Allie.”

It took Hassan a while, but she eventually found herself. And what’s always impressed people who meet Hassan is her determination and sense of self-direction. She’s that person who always finds a way.

“If she ran into a wall, she would go in a different direction,” says Mulu Tamru Saleem, Hassan’s best friend since childhood. “She’s so inspirational in that way, how she doesn’t give up.”

Saleem met Hassan through a mutual friend in seventh grade, and over the years, they grew to become more like sisters than friends.

“Our connection was instant,” Saleem said. “We connected culturally and my family became her family. We literally shared everything. We were joined at the hip.” That meant everything from pooling lunch money to sharing Saleem’s mother’s injera and tibs.

But even with the comfort of Saleem’s family as a surrogate, Hassan had no mother of her own expecting her home on nights and weekends, and in its own weird way, she thinks that gave her the freedom to really come into her own.

“I didn’t have the echo chamber of having to live in an immigrant home, where I had to appease these people at home,” said Hassan, who lived with the family of a basketball teammate in Columbia City for a while. “For better or worse, I got to be the same person all around (all the time).”

Never one to turn down an opportunity, Hassan got involved with youth groups like 4-H and Young Life, and met adults who gave her advice on everything from which summer camps to apply for, to how to keep busy during winter break, to how to comb her hair.

Upon deciding to fully integrate in her community, Hassan started playing basketball and joined a dance team. She tried horseback riding, worked as a day camp counselor at the YMCA and cultivated a network of people willing to help her through life.

“Hawa is just the most easygoing person ever and she loves talking to people, she’s very outgoing,” Saleem says.

Always driven, Hassan graduated early from high school and enrolled at Bellevue College at age 16; around that time, she also began modeling, and her quest to pursue a modeling career took her to New York City. That in turn took Hassan across the globe, and her love of connecting with people helped her build lasting relationships everywhere she went.

Nexus of food and culture

The bonds of family and culture spurred Hassan to pivot from modeling to take on the food world.

After 15 years apart, Hassan finally reunited with her family in Norway in the early 2000s. It was a jubilant, soul-nourishing time, and that extended stay with her mother in Oslo helped Hassan rediscover her Somali roots — and laid the groundwork for her second act: the founding of Basbaas.

In Oslo, Hassan spent hours cooking with her mom. When she returned to Seattle, she stayed with Saleem and her husband and daughters for six months, and continued tinkering with recipes from her mother, perfecting the tamarind date sauce and coconut cilantro chutney that would become Basbaas.

“That was a time where she would take her Vitamix everywhere with her,” Saleem said with a laugh, recalling how Hassan was determined to fine-tune her recipes and ingredients while simultaneously working her contacts in New York in hope of launching her company.

Basbaas was founded in 2014, and Hassan’s food industry career took flight along with her line of sauces.

Hassan met her eventual cookbook co-author Julia Turshen in 2017, when she was making the rounds hosting casual dinner nights that connected immigrants and refugees with lawyers and government officials. She contributed to Turshen’s book, “Feed the Resistance,” in the form of a recipe for suugo, a Somali pasta sauce, and the pair formed a lasting relationship.

Hassan says food has always been a point of connection for her — from dinners at Saleem’s house during her childhood to the blissful reunion with her family in Norway. And she started asking herself questions about her relationship with food and culture.

“How do you talk about African food from a place of integrity?”

“How do you tell worldly stories from a place of allowing others to tell their stories?”

“How do you create room at a table without conforming to an idea of what is good and whole?”

Along the way, she also contemplated the role of women in food and feeding communities: “I never saw them on TV talking about how they cooked and who they cooked for,” Hassan says. Yet, “we’re women who have benefited from the women who’ve cooked for us.”

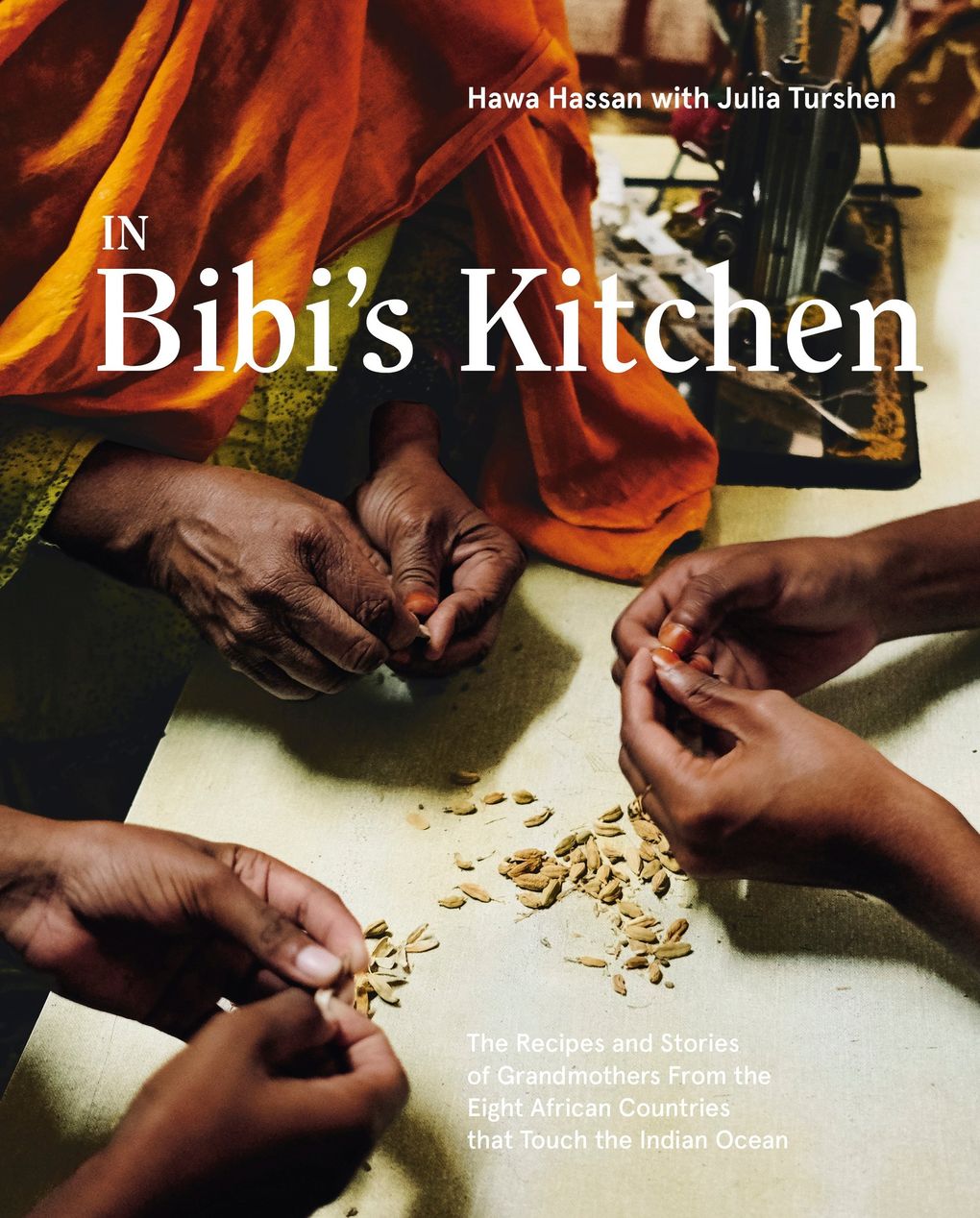

Co-written with Julia Turshen, Hawa Hassan’s cookbook “In Bibi’s Kitchen” was released in October 2020 and has been critically lauded by national media. (Penguin Random House)

Those questions drove the compilation of “In Bibi’s Kitchen,” which was published in October 2020, and has earned rave reviews from The Washington Post, The New York Times Book Review, Vogue and the San Francisco Chronicle. Many of the women featured in the book answer questions about their ideas of home and community. Their answers made Hassan think about her own definitions of those words and their role in her life.

“I’m deeply rooted in the community I live in now,” Hassan says. “The same is true for the little girl I was in Seattle. People were invested in me because I was invested in them.”

This city was a little girl’s entryway to America and played a huge part in shaping the woman Hassan became: “The people that had a huge impact on my life, some lived in my neighborhood and some didn’t. Whether it’s a girl who knows how to be safe in the street, or how to navigate a board, I learned that living in the South End of Seattle,” she says.

With one successful cookbook under her belt, Hassan now hopes to explore her home continent’s relationship with food in more detail with her second project, currently in the works, which will center on civil war and food.

Hassan is also expanding Basbaas to include condiments from other African countries, and there are rumblings about a future television show that will feature Hassan in the kitchen.

Meanwhile, Hassan says she stays busy and maintains her ties with her community by volunteering with nonprofits like The Brotherhood Sister Sol to feed families during the pandemic.