Friday November 9, 2018

By Hannah Beech and Keith Bradsher

Indonesian Navy personnel recovering wheels from Lion Air Flight 610 last week.CreditCreditUlet Ifansasti/Getty Images

JAKARTA — The final moments of Lion Air Flight 610 as it hurtled soon after dawn from a calm Indonesian sky into the waters of the Java Sea would have been terrifying but swift.

The single-aisle Boeing aircraft, assembled in Washington State and delivered to Lion Air less than three months ago, appears to have plummeted nose-first into the water, its advanced jet engines racing the plane toward the waves at as much as 400 m.p.h. in less than a minute. The aircraft slammed into the sea with such force that some metal fittings aboard were reduced to powder, and the aircraft’s flight data recorder tore loose from its armored box, propelled into the muddy seabed.

As American and Indonesian investigators puzzle through clues of what went wrong, they are focusing not on a single lapse but on a cascade of troubling issues that ended with the deaths of all 189 people on board.

That is nearly always the case in plane crashes, in which disaster can rarely be pinned on one factor. While investigators have not yet concluded what caused Flight 610 to plunge into the sea, they know that in the days before the crash the plane had experienced repeated problems in some of the same systems that could have led the aircraft to go into a nose dive.

Questions about those problems and how they were handled constitute a sobering reminder of the trust we display each time we strap on seatbelts and take to the skies in a metal tube.

On Oct. 29, on a morning with little wind, what appears to have been a perfect storm of problems — ranging from repeated data errors emanating from aircraft instruments to an airline with a distressing safety record — may have left the plane’s young pilot with an insurmountable challenge.

On Wednesday, the Federal Aviation Administration of the United States warned that erroneous data processed in the new, best-selling Max 8 jet could cause the plane to abruptly nose-dive. Investigators examining Flight 610 are trying to determine if that is what happened.

Boeing this week issued a global bulletin advising pilots to follow its operations manual in such cases. But to do so, experts said, would have required Flight 610’s captain, Bhavye Suneja, a 31-year-old Indian citizen, and his co-pilot, Harvino, a 41-year-old Indonesian, to have made decisions in seconds at a moment of near-certain panic.

They would have had to recognize that a problem with the readings on the cockpit display was causing the sudden descent. Then, according to the F.A.A., they would have had to grab physical control of the plane.

That would not have been a simple matter of pushing a button. Instead, pilots said, Captain Suneja could have braced his feet on the dashboard and yanked the yoke, or control wheel, back with all his strength. Or he could have undertaken a four-step process to shut off power to electric motors in the aircraft’s tail that were wrongly causing the plane’s nose to pitch downward.

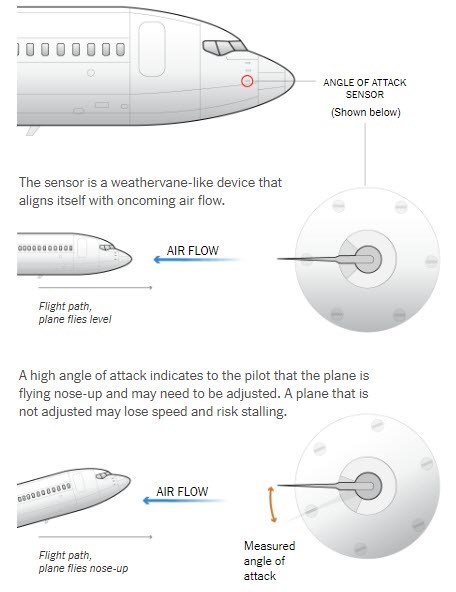

A Critical Sensor

The downed airplane may have received false input from an angle of attack sensor, which measures the angle at which oncoming wind crosses the plane. It is crucial in preventing the plane from stalling.

By Mika Gröndahl

All this would have needed to have happened within seconds — or the aircraft would be at serious risk of entering a death dive.

“To expect someone at a moment of high pressure to do everything exactly right is really tough,” said Alvin Lie, an Indonesian aviation expert and the country’s ombudsman. “That’s why you don’t want to ever put a pilot in that situation if there’s anything you can do to stop it.”

Crowded Skies

Even as ever more people take to the air, flying has never been safer. Last year was the safest in the history of commercial air travel. On average, only one out of every 16 million flights results in a deadly accident, according to the Aviation Safety Network. Nearly a decade has passed since a fatal crash by an American carrier.

Yet as the evidence accumulates, it appears that the fate of Flight 610 may illustrate how a chain of individual events, particularly with highly automated planes, can lead to fatal consequences.

The crash also points to a growing problem in aviation indirectly caused by the advent of low-cost airlines and an explosive growth in the number of people who can afford to fly. While Boeing and its European rival, Airbus, are producing planes as fast as they can, the number of experienced pilots, aircraft engineers, mechanics and even air safety regulators has lagged.

“The problem is, the less-desirable airlines are the ones with the least resources that are scraping the bottom of the barrel in terms of human resources,” said Martin Craigs, the chairman of Aerospace Forum Asia, an industry advocacy group in Hong Kong.

Lion Air’s story began nearly 20 years ago, when an Indonesian travel agent and his brother established it as a carrier that would offer cheap flights between the islands scattered across the country’s densely populated archipelago.

Even as the politically connected company, which owns several airlines, fueled its aggressive expansion with borrowing from banks and government credit agencies, it also racked up at least 15 major safety lapses. Pilots complained that they were overworked and underpaid, and some who challenged the company on contract issues are now in jail.

More troubling, pilots said that the culture at the airline neglected safety. One pilot who refused to fly a pair of planes that he considered unsafe was eventually sidelined by Lion Air and settled his case in court years later.

A former investigator for Indonesia’s National Transportation Safety Committee said that Lion Air repeatedly ignored orders to ground planes for safety issues. Pilots and former safety regulators said that Lion Air flight and maintenance crews regularly filled out two log books, one real and one fake, to hide malfeasance.

Edward Sirait, the general affairs director of Lion Air, said in an interview that the airline considered safety, along with business expansion, its top priorities. He disputed the existence of fake pilot logs.

“They are pilots,” he said. “They are professional.”

Mr. Sirait also said that he had no information about what may have caused the Flight 610 crash. “I am not an engineer,” he said.

Many aviation experts are skeptical of the company. “Lion’s corporate culture is against safety,” said Mr. Lie, the ombudsman. “If they can fly the plane, they will, rather than ground it and figure out what the problem is.”

During the two days before Flight 610 began its final journey, there were repeated indications that pilots were being fed faulty data — perhaps from instruments measuring the speed and a key angle of the plane — that would have compromised their ability to fly safely.

Engineers tried to address the issue in at least three airports, Indonesian investigators said.

After the plane’s penultimate flight, for instance, technicians recorded in a maintenance log that they had fixed the pitot tubes, external probes on the airplane that measure relative airspeed. Earlier that day, on the resort island of Bali, engineers swapped out a sensor that measures the angle at which oncoming wind crosses the plane.

Called the angle of attack sensor, this instrument tells the pilot if the nose of the plane is too high, which could cause the aircraft to stall. In the Max 8, if the data indicates the nose is too high, the aircraft’s systems will automatically pull the nose down.

If the sensor data is wrong, the system could cause the plane to dive.

It is not yet certain if the airspeed sensors and angle of attack sensors malfunctioned on the final flight, or if the computers that process the information coming from the censors malfunctioned.

It is only with further analysis of data on the plane’s so-called black boxes, of which only one has been found, that the cause will be determined.

Still, experts say they are surprised that a plane with known problems was cleared for takeoff again and again. Some say they are aghast, wondering why Lion Air was so cavalier.

“I cannot believe the plane was allowed to fly,” Ruth Simatupang, a former air safety investigator, said of Flight 610’s final takeoff. “It goes against all standard operating procedures.”

Navy divers preparing to search for the wreckage of Flight 610 on Tuesday.CreditEd Wray/Getty

The Last Flight

Before dawn, as the tropical air in Jakarta still hung with moisture, Captain Suneja most likely would have engaged in a ritual familiar to any pilot, walking around the plane that he was to take into the air. He had 6,000 flight hours under his belt, a testament to his diligence during the seven years he had worked for Lion Air.

One of the many mysteries of Flight 610 is why Captain Suneja agreed to fly a plane that maintenance logs should have indicated had two days of airspeed problems — one just a few hours before he was to take off for the small city of Pangkal Pinang, on a tiny, tin-mining island in the Java Sea.

“We want to know why the pilot said yes,” said Ony Soerjo Wibowo, an Indonesian air safety investigator looking into the case. “Maybe me, I would not say yes.”

Could Captain Suneja have felt pressure from a go-go airline to fly a questionable aircraft? Did he not see the maintenance logs that enumerated the problems? Or did he simply not realize that these issues were so serious? Planes experience anomalies all the time. That is why maintenance crews are always on hand and play such a vital role.

At 6:21, long after the first Muslim prayer had reverberated across Indonesia, Captain Suneja took off from Soekarno-Hatta International Airport. Within a couple of minutes, the flight crew radioed Jakarta air-traffic control and requested permission to return, which was immediately granted.

Captain Suneja did not issue a mayday distress call. Nor did he turn back for the capital. Instead, the plane banked sharply left and embarked on a roller coaster trajectory that would have surely terrified the passengers.

In the days following last week’s crash, Lion Air was involved in at least two other missteps — a plane’s wing clipped a pole, and a flight from Malaysia suffered a hydraulic failure upon arrival in Jakarta, according to aviation officials.

The Final Seconds

When the 11th minute of Flight 610 began, the plane was still in nearly level flight at an altitude of about 5,000 feet. By the end of that minute, it had shattered into a kaleidoscope of pieces in the water, after hurtling earthward nose-first at perhaps 400 miles per hour, according to measurements from the Flightradar24 online data service.

What caused the aircraft to tip downward so sharply in that final minute is the greatest enigma. Over the past two days, investigators have been looking into whether it was a maintenance failure or a possible shortcoming in the Boeing 737 Max 8 that could affect other fleets operating the popular jet. Investigators also are exploring the possibility that the pilots were not adequately trained in how the plane differed from earlier models.

Older versions of the Boeing 737 have a reputation among pilots for being easy to adjust the angle of the plane’s nose should a problem arise, said John Cox, the former executive air safety chairman of the Air Line Pilots Association in the United States and now chief executive of Safety Operating Systems, a consulting firm.

Bags with the remains of victims were laid out last week in Jakarta.CreditUlet Ifansasti/Getty Images

But in the new version, Boeing introduced an emergency system that automatically corrects the nose angle to prevent the plane from stalling. In its safety bulletin, Boeing said the system could push the nose down for a full 10 seconds without the pilot’s authorization.

Boeing’s new system was intended to safeguard against what some studies have suggested is the most frequent cause of plane crashes — a stall.

But if the data fed into the system was inaccurate — which investigators are looking into — it could have theoretically caused the plane to pitch forward, presenting even the most experienced pilots with a difficult situation, said Peter Marosszeky, a longtime aircraft engineer and former senior executive at Qantas, the Australian air carrier.

“Training is everything in these situations, and experience is crucial,” he said.

Qantas learned that in 2008 on an Airbus, which has a similar system.

After receiving incorrect readings that appeared to indicate a false stall, an Airbus traveling from Singapore to Perth, Australia, violently plunged twice in automated nose-dives. Dozens of passengers and crew who were not wearing seatbelts were flung about and some broke bones.

In the cockpit, the captain, a former United States Navy fighter pilot, fought the plane into submission and finally managed an emergency landing at a remote airstrip in northwestern Australia.

“It was like a computer gone mad, and the pilots were battling it,” said Geoffrey Thomas, the Australian editor in chief of AirlineRatings.com. He said the skill of the flight crew “saved the day.”

The pilots of Lion Air Flight 610 seem to have encountered a malfunction as well, but with a different ending.

The recommended response issued by Boeing and the F.A.A. this week would not be a pilot’s natural reaction. The flight crew is instructed to switch off the electricity powering stabilizers in the tail of the aircraft that are propelling the downward pitch of the nose.

But without specific training on this anomaly, what pilot would think to turn off part of the plane? When flight crews learn how to helm a new model of aircraft, they typically study the differences between older and newer models. Aviation experts worry that pilots at hard-driving carriers like Lion Air may not be given adequate time for such training.

In addition, differences between models sometimes manifest themselves only after months or years of operation. The Boeing Max 8 went into service just last year. Even though Captain Suneja was an experienced aviator for his age, he would not have had time to fully familiarize himself with the latest version of Boeing’s workhorse jet.

And with only seconds to wrestle the plane out of its fatal plunge, he never got that chance.

Hannah Beech reported from Jakarta, and Keith Bradsher from Shanghai. Reporting was contributed by Muktita Suhartono from Jakarta, Hiroko Tabuchi and James Glanz from New York, and Rick Rojas from Sydney, Australia.

A version of this article appears in print on Nov. 9, 2018 of the New York edition with the headline: Pilots Had Just Seconds to Try To Halt Boeing Plane’s Plunge. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe