Friday March 10, 2017

The figures come as Minnesota joins national debate over the upfront

taxpayer costs of resettling refugees vs. long-term benefits as they

join the workforce.

Getting in the door: Ahmed Farah, 29, resettled in Minnesota last fall

from Somalia with his family and now works overnights at a warehouse.

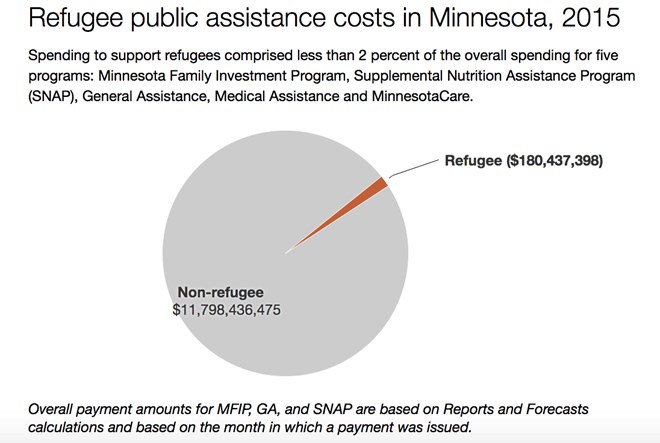

Minnesota chips in

generously to help refugees adjust to life in the United States, but

these costs make up a small fraction of the overall tab for public

assistance programs.

Data the

state compiled for the Star Tribune show that Minnesota spent more than

$180 million in state and federal dollars on cash, food and medical

assistance for refugees in 2015, the most recent period available.

That’s up 15 percent from five years ago but still less than 2 percent

of total expenses for these programs. For state-subsidized child care,

however, refugee communities have come to account for more than a

quarter of costs.

“In the short term,

resettlement can be a very fiscally intensive exercise because of the

kinds of needs refugees bring,” said Ryan Allen, an expert on

resettlement at the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School. “As

people of working age find jobs and become more self-sufficient,

benefits will accrue over time.”

Minnesota

has joined a roiling national debate about how the upfront taxpayer

costs of resettling refugees stack up against long-term benefits as they

join the workforce.

Now, the

Trump administration’s move to pause and shrink the resettlement program

brings fresh attention to the cost question, which Minnesota has never

set out to answer.

Republican

state legislators introduced a proposal last spring calling for an

independent audit of all federal, state, local and nonprofit expenses

for resettlement in Minnesota.

Sen. Bruce Anderson,

R-Buffalo, says the federal government makes all major decisions about

refugee arrivals but passes part of the cost to local communities, where

taxpayers have little clue what they are paying.

“They say, ‘OK, states. You take care of it. You make it happen,’ ” said Anderson, who reintroduced the proposal this year.

In St.

Cloud, retired sales manager Tom Krieg wanted to know what resettling

refugees in Stearns County costs — and he went from the city’s mayor to

county officials to the local newspaper for answers. In response to

queries from Krieg and fellow residents, Stearns County created almost

100 PowerPoint slides on the resettlement process. Krieg says he was

surprised by how few answers were readily available.

“It’s a Minnesota philosophy of, ‘If it looks good and feels good, don’t ask a lot of questions,’ ” he said.

The cost

question is misplaced, some advocates argue. Resettlement is a

humanitarian effort helping some of world’s most vulnerable: single

mothers, people with pressing medical needs, survivors of torture.

To Mark

Sizer, the county’s human service administrator, tackling this question

offers a chance to dispel some misconceptions. He says some residents

asked why refugees get free housing, cars and groceries. They do not.

State bolsters federal aid

New

refugees receive a federal grant of no more than $1,125 to help pay for

rent, furnishings, food and other expenses in their first three months

of arrival. A small number can opt into a federal program that covers

more early expenses, with a push to find a job within four months. The

rest rely on public assistance programs to supplement federal dollars.

Few federally and

state-funded programs here track refugee status. There’s no way to glean

refugee use of unemployment insurance, MNsure insurance subsidies,

Section 8 vouchers and state-run housing subsidy programs, among others.

The state does not know how many refugee students enroll in public

schools.

Over the

past three months, the Minnesota Department of Human Services crunched

the numbers on refugee participation and spending in five assistance

programs at the request of the Star Tribune. Jim Koppel, an assistant

commissioner at the department, says the state doesn’t normally track

these costs because of its commitment to refugees: “We don’t look at the

cost of people coming to Minnesota from Iowa and compare it to the cost

of people coming from South Dakota.”

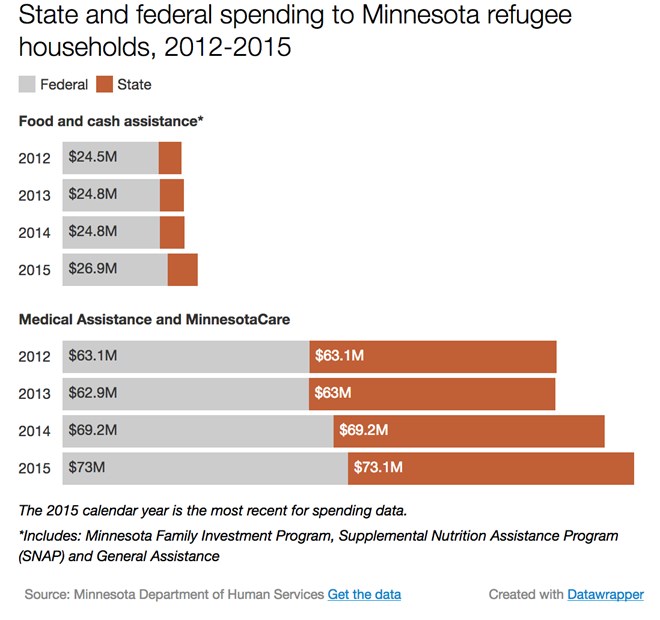

Spending

for cash, food and medical assistance has gone up as refugee arrivals

increased, from about 1,740 refugees five years ago to 2,630 during the

past fiscal year. That includes a 30 percent increase in a cash

assistance program for families with children, which supported about

10,740 refugee households at a cost of roughly $18.2 million in 2015.

The

federal government covered almost 55 percent of the overall costs,

including the entire $15 million tab for food stamps and half the $144.5

million medical assistance bill. The department said the numbers

capture refugees who move to Minnesota from other states as well as most

who become permanent residents after a year in the country, unless they

choose to update their status.

Minnesota is known among newcomers for its generous benefits, says the state’s former refugee coordinator, Gus Avenido.

According

to a federal comparison, refugees in Minnesota receive $532 a month on

average through its family cash assistance program, compared with about

$430 nationally.

State data

show almost 78 percent of Somalis exit the family cash assistance

program within three years, above the 67 percent of all Minnesotans on

average.

Beyond these programs, estimating costs gets trickier.

In response to a data

request, the Department of Human Services found the state resettled more

than 3,785 school-aged children in the past five years. But the state

doesn’t know how many needed English services. In recent years, the cost

of educating English learners was about $9,790 in federal and state

dollars, compared with about $8,080 for an average student.

For other

programs, the only way to estimate refugee participation or costs is to

use home or preferred language — a flawed substitute because residents

who list, say, Somali could be second-generation U.S. citizens or

newcomers sponsored by family.

Using

language as a measure, one program where the state’s largest refugee

communities account for a sizable portion of the tab is subsidized child

care. Almost 7,500 Somali, 300 Oromo and 200 Karen children received

more than $49.6 million in state child care subsidies last year — more

than a quarter of all expenses, compared with 12 percent five years ago.

Counties

have two main resettlement expenses: interpreting and health care

services. But counties like Ramsey, which has overtaken Hennepin as the

top resettlement destination, don’t separate expenses by refugee status.

Stearns County estimated it spent about $80,000 to coordinate refugee

health screenings and more than $368,000 for interpreting.

Ahmed

Farah arrived in the Twin Cities with his sister and parents last fall

after spending almost 20 of his 29 years in an Eritrean refugee camp.

His father, who uses a wheelchair, qualified for Social Security. The

other family members received $250 each in cash assistance and a total

of roughly $400 in food stamps.

When a

warehouse job came along four months later, Farah hesitated. It would be

a shift from teaching math at the camp to manual labor, with nighttime

hours and more than an hour public transit commute from St. Paul to the

southwest metro.

But he says, “I had to accept this. You arrive, and you have many opportunities, but it takes time.”

Now off public assistance, Farah hopes to get into college and restart a teaching career.

A

cost-benefit look at resettlement would factor in refugees’ economic

contributions — and that side of the equation can be even more

challenging.

Concordia

University professor Bruce Corrie points to his study of the Hmong in

the state between 1990 and the early 2010s. The Hmong poverty rate more

than halved, to about 27 percent; the homeownership rate rose from 12

percent to 47.5 percent; and estimated state and local taxes went up

from $9.5 million to $80 million. Corrie estimated the Hmong have

started 3,200 businesses in the state.

“Even if you admit in the short term there are costs, in the long term you come out ahead,” Corrie said.

A

Migration Policy Institute study found refugee men are employed at a

higher rate than their U.S.-born counterparts and refugee women at about

the same rate as the native born. Refugee reliance on public benefit

programs drops off sharply over time, though it remains higher than for

the native born.

Minnesota

also boasts a growing refugee entrepreneurial class. The

Minneapolis-based African Development Center says its member businesses

created 122 jobs and retained 514 jobs last year.

“When

people are thinking about costs, they think short term,” said State

Demographer Susan Brower. “They are not thinking about the long-term

effect on our workforce.”

Staff

writer MaryJo Webster contributed to this report, as did Jessica Bekker,

a University of Minnesota student on assignment for the Star Tribune.