Monday February 13, 2017

Incumbents losing elections and graciously conceding are not what most associate with Africa, let alone Somalia. By contrast, the Kenyan experience is rather typical. Here, no incumbent President has ever lost an election. Whether by hook but more often by crook, they manage to cling onto until either the end of their terms or their lives, whichever comes first.

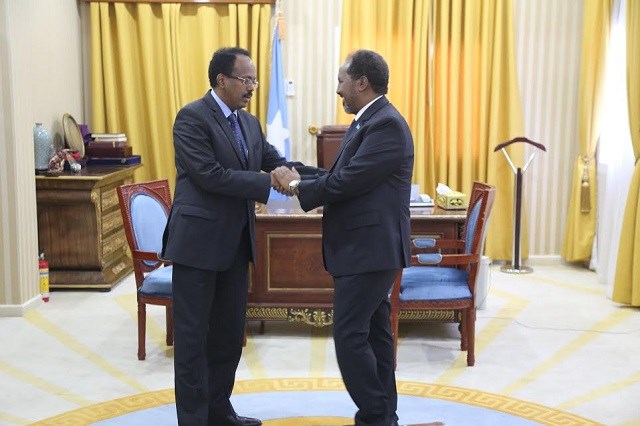

But that is exactly what happened in the Somali capital on Wednesday. The election of former Prime Minister Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo as the country’s ninth President upheld a rather curious, perhaps unique tradition: Somalia has never reelected an incumbent as President.

It’s a tradition that goes back to the founding days of the Somalia republic. In its first election following independence and unification in 1960, the popular Aden Abdullah Osman Daar was elected President. Seven years later, he would become the first African head of state to peacefully hand over power to a democratically elected successor — his former Prime Minister Abdirashid Ali Shermarke.

Now this week’s election in Mogadishu was not, by any stretch of the imagination, one to be emulated. Due to the ongoing terrorist insurgency perpetrated by the al Qaeda-allied al Shabaab, universal suffrage was out of the question. Instead, 135 elders picked 14,000 delegates who elected 275 MPs and 54 senators who in turn elected the President.

The process was marred by allegations of corruption, vote buying and intimidation, which is perhaps not surprising for a country that ranks at the very bottom of Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. The head of the country’s police publicly supporting the incumbent and security concerns led to both the shut-down of transport in Mogadishu, and the moving of the election to the airport, which is secured by Amison. Much of this would be familiar to Kenyans as our own general election looms.

Though not as dire as that of our neighbour, our system is not without its controversies. There are credible suspicions of attempts to steal it right from the voter registration stage, with public officials, especially chiefs, illegally co-opted into an effort to help boost registration numbers in areas perceived as supporting President Uhuru Kenyatta’s Jubilee Party. Further, our global corruption ranking is not that much higher than Somalia’s and the expected deployment of thousands of police and security agents to safeguard the election spoke not just to the legitimate security concerns in the wake of our invasion of Somalia, but also to the government’s fear of its own people.

President Uhuru recently said he is willing to peacefully hand over power if he loses and to his credit, he has already delivered a historical first: In 2002, he became the only losing presidential candidate from a major party in Kenya’s electoral history to deliver a concession speech. Whether he will remain true to his word remains to be seen, but, as Somalia illustrates, the fact of a chaotic and problematic electoral process need not preclude it.

Somalia also provides an object lesson in the dangers of the ethnic mobilisation and military takeover of civilian affairs. Despite being one of only two largely ethnically homogenous sub-Saharan African states, fragmentation along clan affiliation is one of the main reasons the civil war has persisted for so long. Kenya itself had a taste of it in the violence that followed the disputed elections of a decade ago.

Another factor in Somalia’s disintegration was the military takeover that followed the assassination of President Sharmake in 1969. The Siad Barre dictatorship hat followed set the country on the path to destruction. Kenyans should therefore be wary of occurrences that diminish civilian control over the military or give it a taste for civilian responsibilities. In that regard, the decision by President Uhuru to appoint Chief of Defence Forces Gen Samson Mwathethe to chair a committee overseeing the implementation of government projects should be of concern as should the seeming inability of civilian authorities to hold the military to account following the debacles at Westgate, El Adde and, most recently, Kulbiyow.

Somalis are a fiercely independent-minded lot, not as reticent in expressing their opinions as Kenyans are generally perceived to be. “Every man is his own Sultan” is how one 19th Century visitor described them. Richard Dowden, Director of the Royal African Society, in 2011 recounted an incident in which a waiter publicly berates a government minister in a restaurant in Hargeisa, capital of the northern breakaway — and far more peaceful — Somaliland republic. Such a scene would be unlikely to be repeated here (except perhaps on our famously noisy online platforms). But maybe we could learn from that waiter the value of confronting, rather than accommodating, our lying and thieving politicians.