Saturday, October 20, 2012

By CHARLOTTE EAGAR

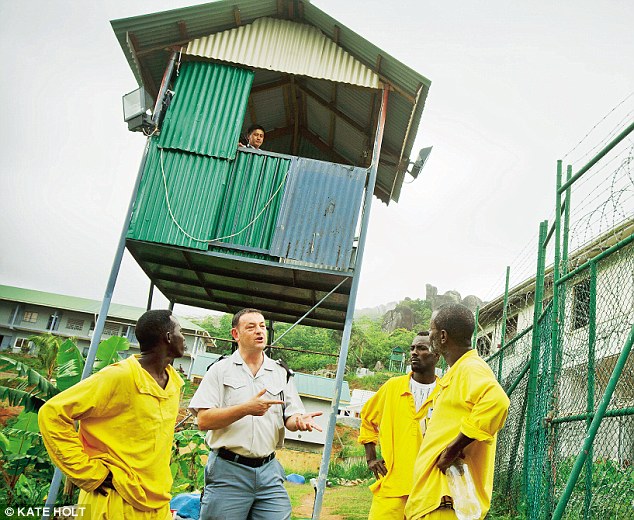

Will Thurbin poses at Montagne Posse Prison with his dog Lucy, while prisoners look on. He's a former governor of HMP Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight, the prison that once housed the Krays and Ian Brady

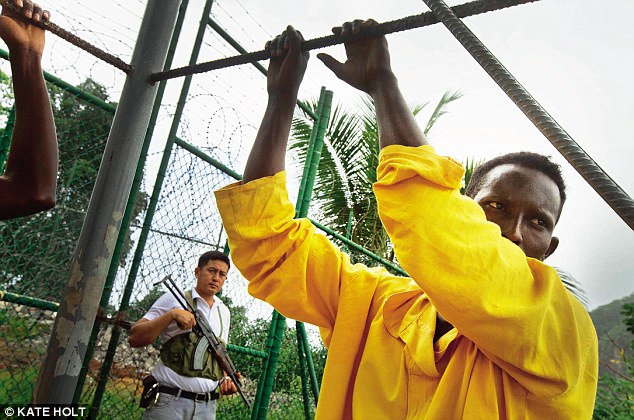

Behind the 15ft high razor wire, a huddle of men in yellow jumpsuits sit on their haunches, while others stand staring blankly into space.

Armed guards wander among them and keep watch from a rickety corrugated-iron watchtower.

This hilltop compound, surrounded by jungle, is Montagne Posse prison, which is Creole for ‘Mountain Rest.’

Some of the prisoners face a rest here of up to 22 years. Many are Somali pirates, imprisoned hundreds of miles from home in the Seychelles, under the guard of 47-year-old Will Thurbin.

He’s a former governor of HMP Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight, the prison that once housed the Krays, Ian Brady and Peter Sutcliffe.

‘We’ve got about 100 pirates here,’ he says.

‘They are a mixture, some convicted and some still on remand, who can wear their own clothes.

'Their sentences vary, depending on their behaviour at the time of capture, whether or not they resisted arrest.’

Over 20,000 ships pass the Horn of Africa annually, and the cost to the international community from piracy has been estimated at £4.1 billion a year.

According to the International Maritime Bureau Piracy Reporting Centre there have been 70 attempted hijackings already this year, and 13 ships have been taken hostage.

Although most of the prisoners at Montagne Posse were caught in the Indian Ocean in little skiffs carrying AK-47s, rocket-propelled grenades and ladders rather than fishing nets, they still claim to be fishermen.

Montagne Posse prison is set in remote mountain scenery. Some of the prisoners face a rest here of up to 22 years. Many are Somali pirates, imprisoned hundreds of miles from home in the Seychelles

That’s even after they have been convicted in UN-funded courts in the Seychelles – where two British Crown Prosecution Service lawyers are currently working.

There is a huge multinational naval operation to prevent piracy, but the problem has always been that even if pirates were captured their guilt was hard to prove, and then no one knew what to do with them anyway so they would be freed and allowed to return to piracy.

The UK is spending £9 million on helping detain and prosecute pirates.

And a new Regional Anti-Piracy Prosecutions Intelligence Co-ordination Centre is due to open here in January 2013, funded largely by the British taxpayer.

Piracy now is organised crime and there is concern that it could diversify into drugs, so their focus will move to the kingpins.

It will be fronted by Garry Crone, a senior Serious Organised Crime Agency officer, on secondment to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Piracy has become big business. In Somalia there are men who have made serious money, crime overlords laundering fortunes round the Gulf, and Britain is helping hunt them down.

‘These people are not a slightly more menacing version of Johnny Depp,’ says Crone.

‘It’s organised crime, with hierarchy, structure, a rewards basis, and strategic alliances between the groups.’

The Seychelles may have been the tropical honeymoon idyll of choice for the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, but there’s trouble in paradise.

The economy, based on fishing and tourism, was in danger of being ravaged by pirate attacks. Their fishermen could not fish after several boats were taken hostage, and yachts and cruise liners no longer risked coming to their jungle and coral islands.

‘Our revenues from fishing and tourism fell 30 per cent in 2009,’ says Joel Morgan, the Seychelles Transport and Interior Minister

Even worse, the Seychelles imports 90 per cent of its food and fuel, and insurance premiums for delivery went up by 50 per cent. The result was soaring inflation. Then a tanker with vital supplies of cooking gas was taken hostage.

‘We were within a couple of days of running out of gas,’ says Morgan.

A Somali prisoner at Montagne Posse. 'The costs of rehabilitation are great but the human costs of doing nothing with prisoners to reduce their reoffending are greater,' said Thurbin

In March 2009, a Seychelles yacht, the tourist charter Indian Ocean Explorer, was captured in the country’s territorial waters.

The tourists on board had left the boat earlier that day, but the captain, Frais Roucou, and his crew were forced to sail to the Somali coast, where they spent 88 days in captivity before being released when a ransom was paid.

The Seychelles realised it was under attack, so the government decided to volunteer its courthouses and prisons to put on trial and incarcerate Somali pirates captured in the Indian Ocean.

But under new EU law, any pirates captured by European navies could not be sent to a country for trial where the prison and the justice system were not up to EU human rights standards.

It was also thought, under UK law, that pirates captured by British ships had to be brought before a British magistrate within 48 hours, which was impossible from a warship in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

The alternatives were either to hang the pirates from the yardarm, or just keep releasing them, unless a country around the Indian Ocean could be found with a suitable justice system and the inclination to help.

‘It was a mutual understanding that the Seychelles would take this part of the burden – bringing the pirates to justice,’ says Morgan, in his office close to the old British colonial courthouse where suspected pirates are now tried.

The legal process was helped by some bright spark noticing that the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea could be interpreted to mean that, since piracy was an international crime, pirates could be tried anywhere – and the clock on getting pirates in front of a magistrate only started ticking once they hit dry land.

'We hope to be self-sufficient in vegetables by next year. Growing vegetables is a useful skill for the prisoners when they leave. I want to set up art classes as well,' said Thurbin

It was this decision by the Seychelles government that brought Will Thurbin here from his family home in the Isle of Wight as a UN mentor to their prison system.

This year he has been working directly for the government. Until recently there were also six British prison officers working here on secondment.

‘The British prison system is a good model for us,’ says Morgan.

‘We are a former British colony, so our judicial and prison systems were modelled on the UK’s in the past – it’s just that ours had got left behind.

'We have received legal assistance for our criminal justice system and through the UNODC trust fund the UK is providing money to rebuild the infrastructure in the prison.

'They are also helping to expand the capacity of the police.’

Montagne Posse is not the only pirate prison the UK is financing.

We have also provided $800,000 to refurbish a prison in Bossaso in Puntland, a relatively stable region of Somalia; $1,050,000 to build a new prison academy and Ministry of Justice in Garowe in Puntland; and $400,000 to refurbish a prison in Hargeisa in Somaliland, another reasonably stable area.

The governor of Hargeisa, John Wilcox, is another ex-governor of Parkhurst.

According to Morgan, the intention is that as soon as there is an adequate prison structure, all the pirates in the Seychelles will be sent back to Africa to serve their sentences.

But is this all money well spent? Lindsay Skoll, the new British High Commissioner in the Seychelles, is keen to point out our strategic interest.

‘Piracy is a global problem but it affects our national and commercial interests. Ten per cent of our oil and 50 per cent of our gas is imported from Gulf states and is transported through the Gulf of Aden.

‘We’re spending £4 million over three years on maritime security throughout the region, including the Horn of Africa.

'Perhaps this is just something we are very well suited to: judicial reform, prison reform.

'The UK takes a holistic view of piracy – who and where are the financiers, who are the big kingpins and what are the root causes?’

Will Thurbin proudly takes us on a tour of his manor, pointing to Montagne Posse’s garden.

‘We hope to be self-sufficient in vegetables by next year. Growing vegetables is a useful skill for the prisoners when they leave. I want to set up art classes as well.’

He misses his home, his wife Jane, his two sons, and the family lurcher, although a dog near the prison has adopted him.

‘This is going to be the volleyball court and five-a-side football pitch,’ he says, pointing to a patch of Tarmac littered with piles of fencing and concrete blocks.

‘Exercise is important for getting rid of aggression. We’ll have a timetable for who can use the gym.

'The prisoners need structure in their lives.’

So far the renovation works – a new 60-cell block, a sewage recycling block, a fish preparation centre and kitchen, a planned auditorium, the gym and multi-faith room and the volleyball court – have cost the UK taxpayer nearly £400,000 ($600,000).

The prisoners are also all learning English and now get two square meals a day – huge plates of rice with fish or chicken and vegetables.

‘Some of them are very thin when they arrive, and they are quite relieved when they realise they are going to be well looked after.’

Thurbin rejects accusations that he is too soft on his inmates.

‘Some people believe prisoners should be locked up and the key thrown away. I point out that the majority of prisoners will be released back into our communities at some point.

'If nothing is done with them they are likely to reoffend, create more victims and come back into prison. One of the victims might be them or a loved one.

'The costs of rehabilitation are great but the human costs of doing nothing with prisoners to reduce their reoffending are greater.’

We pass three Somalis chopping undergrowth beneath a retaining wall, as part of the renovations; one, an older man called the ‘Captain’, says: ‘I’m just a fisherman.’

The young guys start giggling, but the Captain says crossly: ‘I’ve been a fisherman since I was 18. I’ve never been a pirate. But the EU ships stole all our fish.

'There is no government in Somalia to patrol our sea. We don’t know what the future holds for our country.’

This is the Somali excuse – and perhaps for the Captain it has a nugget of truth – although he has obviously made some serious money, since he is keeping three wives and 18 children on his savings while he’s serving his sentence.

Far below Montagne Posse, by the sea, Garry Crone shows me around the building site that will soon become his new headquarters, the Regional Anti-Piracy Prosecutions Intelligence Co-ordination Centre, towards which the UK has contributed £550,000.

Thanks to the internet and mobile phones, organised crime, like the rest of the economy, is becoming globalised.

‘We could probably have done this from the UK,’ says Crone, ‘but we’d lose a major opportunity to train regional police officers to deal with transnational organised crime.

'We’re starting to see heroin come down to the coast of Pakistan for shipping across the Indian Ocean to Kenya.

'A skiff was stopped the other day with a couple of hundred kilos of heroin on board.’

Crone is aiming for a centre of 28 members of staff: ‘Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands are involved, as are the U.S. Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, the UAE and Mauritius are already here working with us, too. We’ve got ongoing discussions with France but that’s a little bit up and down. ’

The great fear, not publicly voiced, is that piracy may spill over into terrorism. So far, the official line is that the pirates and the terrorists don’t get on, but it seems likely that the terrorists are trying to grab some of that pirate gold for themselves.

The solution, everyone agrees, is peace in Somalia – piracy won’t stop until the pirates have alternative jobs, and their hostage ships can no longer lie with impunity off Somalia’s coast.

The Department For International Development has announced plans to spend £63 million a year in aid in Somalia until 2015, of which 40 per cent will go to help shore up the stable autonomous region of Somaliland.

Back on the mountain top, Daud, a twentysomething pirate, explains he used to be a water engineer.

‘But there were no jobs in Mogadishu,’ he says.

Is that why you became a pirate?

‘I’m not a pirate. I’m an illegal immigrant, like those people leaving Libya. I was trying to get to South Africa to find a job.’

Perhaps by the time Daud gets out – in six years’ time – with his gardening skills and fluent English, there will be a Somalia ready to employ him again.