|

| Air Force Col. Dan Shoor listens to a young Somali refugee’s cough at a Djiboutian clinic, stretched to its limits because of an influx of 5,000 refugees. Malnutrition is a widespread problem, as are sanitation woes and influenza. About five children in the community of 12,000 die each day, one Army sergeant estimates. CHRIS TYREE PHOTOS / THE VIRGINIAN-PILOT |

Sunday, January 28, 2007

ALI ADDÉ, Djibouti — A curious crowd of women and men in billowing skirts streamed toward the landing zone as two U.S. Marine helicopters touched down on rocky African desert.

The Marines had pistols strapped to their legs, but the choppers from New River Marine Corps Air Station in North Carolina were doves, not hawks.

Inside were an Air Force doctor and a team of Army civil affairs specialists on a mission to bring help – and hope – to 12,000 Somali refugees.

The forbidding landscape is a 20-minute flight – but seems a world apart – from Djibouti’s capital city, where the U.S. military has established a base, Camp Lemonier.

U.S. air strikes on suspected terrorists in Somalia this month called the world’s attention to the region.

However, the U.S. military has been quietly engaged in the Horn of Africa since 2002, using about 1,500 troops to build schools and medical clinics, dig wells, treat sick people and inoculate livestock. Dozens of Navy sailors and officers from Hampton Roads are part of the force, and more are preparing to head to Djibouti in early February.

With its mission to win hearts and minds through goodwill, this unorthodox military

operation looks more like the Peace Corps than the Marine Corps. But the effort is primarily to deter al-Qaida and Muslim extremists from spreading throughout a region rife with poverty and despair.

“Our mission is not capture and kill,” said Rear Adm. Timothy Moon , deputy commander of the Navy-led task force.

Moon, a reservist from Suffolk, calls it an experiment. “I hope it works.”

There’s reason for the United States to worry about terrorists in Africa.

In three of the eight countries where the task force labors, al-Qaida has orchestrated anti-American attacks. U.S. embassies were bombed in Tanzania and Kenya in 1998, killing 250 people. And 17 Norfolk-based sailors died in a blast that crippled the destroyer Cole in Yemen’s Gulf of Aden in 2000.

Here in Ali Addé, the military visitors toured a newly refurbished health clinic about the size of a gas station. Renovated by the U.S. Agency for International Development, the tidy facility had a closet-sized pharmacy and a few exam rooms.

About 75 women gathered on the porch, ailing children in their arms. The wait was long. One toddler played with a discarded surgical glove blown up into a hand-shaped balloon.

Sgt. 1st Class Charles Parnell, a broad, balding Army reservist – and a police officer and paramedic in Cleveland in his “other” life – said a recent influx of about 5,000 refugees from war-torn Somalia had taxed the resources of this clinic and another nearby, which ran out of medicine.

Hungry people boil the bark of scrubby trees and bushes to soften it, then eat it. Chronic malnutrition, influenza and poor sanitation are the main scourges, said Parnell, his face and voice filled with distress.

He estimated that one to two women in this community die each week from diarrhea, pneumonia, tuberculosis, malaria or asthma. Children perish, about five a day, Parnell said.

Fatouma Ali desperately hoped her son would not become one of them.

Ali held her toothless, feverish 2-year-old beneath the bright orange shawl she wore. She didn’t know her own age – she guessed 45. She gave birth to her first child 11 years ago; five more children followed.

Through a translator, Ali said her family fled Somalia at the beginning of Ramadan last fall, coming to Djibouti in a car loaded with as many possessions as they could fit.

“Here is a peaceful country, and everybody wants to live in a peaceful area,” Ali said.

Somalia hasn’t had an effective central government since 1991, when warlords toppled dictator Mohamed Siad Barre and then began battling among themselves. Al-Qaida has moved in, prompting the U.S. airstrikes this month.

The clinic is another way to keep al-Qaida at bay. Here, a volunteer nurse and a local physician typically see as many as 50 patients a day. Air Force Col. Dan Shoor, dispatched here from Alaska, sometimes helps.

In an exam room with unscreened windows overlooking craggy mountain peaks, Shoor diagnosed a 3-year-old Somali child with pneumonia and an underlying case of tuberculosis.

Back home, Shoor would have prescribed antibiotics for the pneumonia, as well as a nine-month regimen of drugs for the TB. Active cases of TB often require at least four different drugs administered simultaneously.

Shoor said the child would get antibiotic treatment, and the clinic nurse also would try to treat the boy’s relatives, who probably have latent cases of TB.

He viewed the child’s odds of survival as even.

About 800,000 people in the region suffer from the infectious lung disease, Shoor said. Some are infected with strains resistant to multiple drugs. Sometimes, there is little doctors can do.

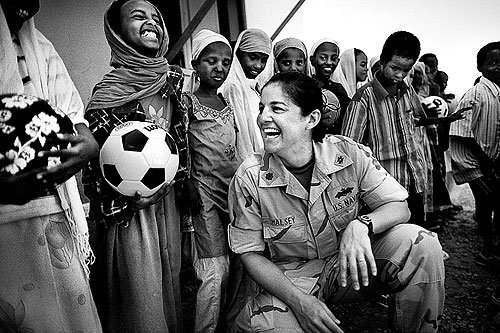

A former goalie on Stanford’s soccer team, Navy Lt. Cmdr. Wendy Halsey, left, had relatives and former teammates send her soccer balls to distribute at Djiboutian schools. |

Children are often the focus of military missions in the Horn of Africa. Besides receiving medical care and new schools, they are the subject of sports diplomacy.

Navy Lt. Cmdr. Wendy Halsey said that everywhere she went during her six months in Africa, she got the brightest smiles when she handed out soccer balls.

Halsey, a Navy Seabee and former goalie on Stanford University’s soccer team, took that as a cue and asked former teammates, relatives and friends to send balls in lieu of the usual care packages.

On a recent trip, Halsey and a three-car caravan of military officers and translators headed into downtown Djibouti.

The neighborhood around the first school was like many in the capital city, population 400,000. Goats meandered through dirt streets; barefoot children wandered amid shacks made from scraps of wood and metal. No grass, no yards, no electricity or running water, but plenty of garbage along every street and lot.

Halsey and her colleagues stopped first at Ecole de Tour- Ousbo Primaire Publique, which serves 1,200 students. Half attend class in the morning, the other half after lunch – typical in Djibouti, where there are too few schools to accommodate everyone at once.

The camouflage-clad Americans filed into the one-room library. Its simple wooden shelves held books in French, the official language of Djibouti since its days as a French colony.

In the middle of the room, on child-sized desks, were five personal computers donated by the Chinese government . China also is vying for influence in the Horn of Africa, parts of which have ample oil supplies.

After exchanging pleasantries, sipping sodas and sampling fried dumplings, the group got down to business.

“I have, like, 15 soccer balls,” Halsey told the principal through a translator. “What’s the best way to hand them out?”

The principal decided the balls would stay at the school for everyone to use. Teachers brought one class of second-graders – 52 in all – into a dirt courtyard next to a crumbling concrete building.

Excited chatter filled the air.

Halsey handed balls to some students and kicked shiny new ones toward others, making sure not to overlook the girls.

When this tall, vigorous woman with dark braids looked directly at the shy girls, their faces flickered with smiles. Then their lips would reclaim their teeth, and they would look away.

For another Seabee on the outing, Lt. Cmdr. Ra Yoeun, the goodwill outing held extra meaning.

As a 10-year-old orphan in a Cambodian refugee camp on the Thai border in the early 1980s, Yoeun remembers similar gifts from United Nations officials.

“It’s kind of coming full circle,” he said.

Members of an Army Reserve unit from Montgomery, Ala., fix a well in a tiny village in November. The well’s chain had been rusted through by corrosive water, rendering the pump useless for several months. |

Youen and Halsey represent the changing face of the Horn of Africa task force.

After nearly four years of war in Iraq and five in Afghanistan, the Army and Marine Corps are spread thin. Last spring , the Navy took control of the African peace-waging mission from the Marines.

The land-based effort is led by Rear Adm. Richard Hunt , who once commanded an aircraft carrier strike group.

The next wave of Navy brass – many from the Norfolk-based Second Fleet – head to Djibouti next week . Many spent four months prepping at the Joint Forces Command in Suffolk.

The Combined Joint T ask F orce – “joint” because it involves all branches of the U.S. military and “combined” because about a dozen military advisers from Europe and Africa help plan the missions – is at heart a civil affairs undertaking.

The occupation of post-war Europe and Japan in the 1940s and 1950s is a prime example of military civil affairs, as the services oversaw the rebuilding of gutted cities, the drafting of new laws and instituting of local governments.

Since then, civil affairs has been an oft-overlooked specialty. Until Djibouti, the Navy has had no such job.

C ivil affairs troops at Camp Lemonier, the only U.S. military base in sub-Saharan Africa, are the equivalent of infantry troops in a war zone: They’re the ones who go out and do the work.

“We studied about this kind of nation-building when I was going through initial training, and now we’re actually doing it,” said Army Sgt. Roberto Fernandez , a high school history teacher in Lauderdale Lakes, Fla. “What we’re doing out here is completely different.”

He is encouraged by little things, such as a comment from a man in the village of Dorali, where Fernandez worked on a project last year.

“One of the villagers said, 'You guys have been here only six months and you’ve already done more for us than the French have done in 100 years.’ ”

On the same day Parnell and Fernandez flew to Ali Addé , an Army Reserve unit from Montgomery, Ala., finished a project in a village outside the mountain town of Arta.

The 334th Engineer Detachment had been repairing a well drilled by a U.S. unit in 2003. It was a simple contraption – a hand pump brought up water from about 120 feet, serving both the nomadic herders and, through a separate trough, their goats and sheep.

But after three years, Army Capt. Rachel Honderd said, corrosive water and a broken chain had rendered the pump useless. For five months, the community hadn’t gotten a drop from the well, forcing villagers to move their animals elsewhere.

“Water is one of the most important things we deal with in the Horn of Africa,” Honderd said. “When we show up, they get very excited.”

In less than two days, the Army unit found a fix and got water flowing again. The engineers planned to return to convert the hand pump into a solar pump that will require less maintenance and serve a larger population.

The military also is compiling a hydro geological database, so incoming units can more easily determine where to sink new wells. Sixteen more wells already have been approved for Djibouti and Kenya, Honderd said.

Petty Officer 2nd Class Jared Woodall shows Ahmeed Med Ali, 15, how to lift weights. A native of Oxford, Miss., Woodall's six-month tour in Africa made him curious about his heritage. "Now, I want to know where my roots come from," he said. |

Sometimes the targets of U.S. outreach are accidental – or at least unscripted.

On the eastern edge of the city of Tadjoura, next to a broad, dusty soccer field, a unit of Navy Seabees is building a middle school.

The sailors are accompanied by an Army National Guard unit from the U.S. territory of Guam. The soldiers don’t do much patrolling; instead, they mentor teenagers. They usually can’t speak the same tongue, but their body language needs no translation.

Spc. Joevince San Nicolas taught himself enough of the Afar language to make the children giggle when he barks it out.

He taught them to march to military cadence.

He had them clear rocks off the school’s dirt basketball court.

He makes them run sprints when they quit listening to him – but they don’t run alone.

“Whatever they do, I do with them,” San Nicolas said. “Whoever does it best, I give them money to go buy ice cream.”

The airborne soldier – he parachuted into Iraq with the 173rd Airborne Brigade at the beginning of that war, when he was on active duty – much prefers serving here.

“You can see how you’re helping, and people are appreciative,” he said. “It’s not that you give today and they attack tomorrow.”

Others mentor in different ways.

Jeramie Chew , a Navy corpsman from Portland, Ore., noticed that Djiboutian children are more aggressive toward one another than their American counterparts. Older kids regularly gang up on younger, weaker ones.

Within arm’s reach of Chew hovered a deaf boy, his bright orange T-shirt contrasting with Chew’s bland uniform.

“He’s picked on a lot,” Chew said of the boy he knows as Adida – a name he’s not sure how to spell. “I stand up for him.”

He’s trying to teach Adida not to throw rocks at his tormentors.

Chew and Adida bond using hand signals and cold sips of Coca-Cola out of glass bottles.

“I think half the time we don’t know what we’re saying to each other, but it’s all in good fun,” Chew said.

Staff Sgt. Tifani Kent, an Air Force nurse, cradles a child in late November at the Sisters of the Nativity Convent Orphanage in Djibouti’s capital city. About 50 children live at the orphanage at any time. |

A few days after the school visit, Yoeun joined Halsey and a group of enlisted personnel on a biweekly trip to play soccer and kickball with the residents of a nearby boys orphanage.

It shares space with a trade school, and the wide-open area behind the decrepit buildings sits in view of Camp Lemonier’s guard tower.

The orphanage, housing 25 to 30 boys, had been adopted by the chaplains at Lemonier and received money from a base pie-in-the-face contest.

Petty Officer 2nd Class Gregory Bennett , a religious program specialist from Oceana Naval Air Station in Virginia Beach, took visitors toward a putrid bathroom thick with stink and flies.

The base E-5 club – Navy petty officers second class or Army sergeants – had raised $13,000 to renovate the bathroom and install running water and flush toilets.

Other projects also were in the works.

The facility had no beds, just a few grungy mattresses on the floor. Bennett shepherded a small group of military members into a room where long, cardboard boxes containing new beds were waiting to be assembled. Blankets and pillows were on order from the camp’s exchange.

Bennett’s group headed toward the shrieks and shouts near the basketball court. There, about 20 soldiers, sailors and airmen in T-shirts and shorts, looking like the American 20-somethings they are, played kickball, basketball and soccer with whoops of glee.

Halsey hadn’t had time to change out of her uniform and boots, but the Navy officer and mother of three played energetically anyway, running and grinning in the desert dusk.

She was one of many people who would finish their day marveling about this military mission few Americans have ever heard of, working in ways she’d never dreamed.

What none of them could know – and probably won’t for decades – is whether this experiment to stop the spread of terrorism in the Horn of Africa worked.

Source: Pilot Online, Jan 28, 2007