Wednesday December 14, 2022

By ABDIRAHMAN MOHAMED and BECKY Z. DERNBACH

Qudbi Dayib, the president of Dar-Us-Salam Center Mosque, helped to facilitate the Somali Parent Committee meeting at Burnsville schools. Qudbi attempted to quell parent fears after one mother shared a worksheet with a rainbow on it. 300 parents had gathered to share their fears about LGBTQ issues in Burnsville schools. Credit: Abdi Mohamed | Sahan Journal

Typically, about a dozen parents attend the monthly meetings of the Somali Parent Committee for Burnsville-Eagan-Savage schools. On Monday night, amid concerns about a policy the district says is intended to protect transgender students, more than 300 were there.

The school district moved up the date of the December meeting to address community fears about the policy and what officials say is outright misinformation. The policy was approved as many schools grapple with concerns about LGBTQ mental health, and Burnsville-Eagan-Savage reels from the recent suicides of two district high school students. But Somali parents worried that the policy means schools would conceal information from them about their children.

“I’m a mother, I’m not an advocate, but I advocate for my kids,” Maryan Gutale, a mother of five district students, said in an interview. “I’m having these conversations with my daughter and talking with her about the fact that people have a different way of life than us, and that’s OK. We have our faith and beliefs, they have theirs. But for some parents, outrage is enough for them as a response.”

Attendance at Monday’s meeting was four times higher than it was at a school board listening session on the same topic, held December 8. While parents had initially questioned whether the schools would withhold information about their children’s gender identity, by Monday the concerns had ballooned to include many issues relating to the LGBTQ community. District staff fielded questions from parents for more than two hours with the help of Somali-speaking staff members. They explained current school procedures and policies to correct misinformation while explaining the reasoning behind existing policies and the importance of supporting LGBTQ students.

In recent days, social media platforms and WhatsApp group chats in the Somali community have been afire with rumors that school staff would give students hormonal treatment as part of gender-affirming therapy without parents’ knowledge or permission. (In reality, schools cannot give medication of any kind without parental consent and a medical plan.) These rumors stemmed from an article on the conservative website Alpha News that ran a misleading headline stating that Burnsville schools will conceal the gender identity of children from their parents. From there, district parents and the wider Somali Muslim community in the Twin Cities grew concerned that educators were not just leading children to accept trans and queer individuals, but also encouraging children to change their own gender and sexual identity.

The previous week’s listening session was characterized by a civil tone: Parents asserted they supported the LGBTQ community, and wanted a tweak of the policy to better accommodate their rights as parents. Instead of cooling passions, however, Monday’s parent meeting was more emotionally charged and driven by fears that were seemingly stoked online. Also, unlike last week’s meeting, parents did not establish a clear goal. At times, the meeting took the form of a venting session for parents to air frustrations and repeat questions.

The meeting was designed as a forum for parent discussion, not a decision-making space, so no clear next steps emerged.

Questions and answers

Superintendent Dr. Theresa Battle and Assistant Superintendent Chris Bellmont took questions through a Somali interpreter. Somali district staff passed a microphone around to parents. Some repeated questions that had already been asked; others used the platform to make speeches about how to best move forward. Some threatened to take their children out of the district’s schools unless the policy was changed.

The room, which had a capacity of 237 people, filled up in the first few minutes of the meeting. District staff opened a second room for parents, to provide overflow space. District staff repeatedly told parents that the policy stemmed from a 2013 law and that they had no control over decisions at the Minnesota Legislature.

Typically, about a dozen parents attend the Somali Parent Committee for Burnsville-Eagan-Savage schools. On Monday, more than 300 showed up. Credit: Abdi Mohamed | Sahan Journal

One mother shared her appreciation for the school staff at Gideon Pond Elementary School and asked how they were implementing the new policy. “Islam does not support the LGBT movement,” she said, receiving enthusiastic applause. She continued to say that as a Muslim parent she doesn’t hate anyone and that she would even protect children who identify as LGBT. She added that teachers have a major influence on students and that their time could be better spent on other topics.

Some parents questioned the protocols for transgender students using bathrooms at school. Bellmont explained that district staff allow students to use bathrooms that align with their gender identity. “We do not check our children’s gender,” he said. Only once in his 15 years in the district has a child asked to use a different bathroom, he added.

A father raised his hand and took the microphone. “What age does the district think is mature enough for a child to have their request about their gender identity taken seriously?” he asked. “Would a 4-year-old’s request be validated by a staff member, without a parent knowing?”

Several parents asked whether schools could administer hormonal medication. Battle, the superintendent, told them that nurses cannot administer medication to students without a prescription from a physician and consent from parents. “The school cannot even give a student Tylenol,” she said.

In response to questions about books depicting same-sex couples in classroom libraries, Battle said those families have just as much of a right to see themselves in the curriculum as anyone else. “We’re not going to hide LGBT people by not including them in the literature as if it’s not something normal,” she said.

Cynthia Sampers, the district’s director of early childhood programs, explained that the district strives to provide positive images of every student’s background in the classroom, whether through a book or photos in the room. The books are not required to be read to every student, she said.

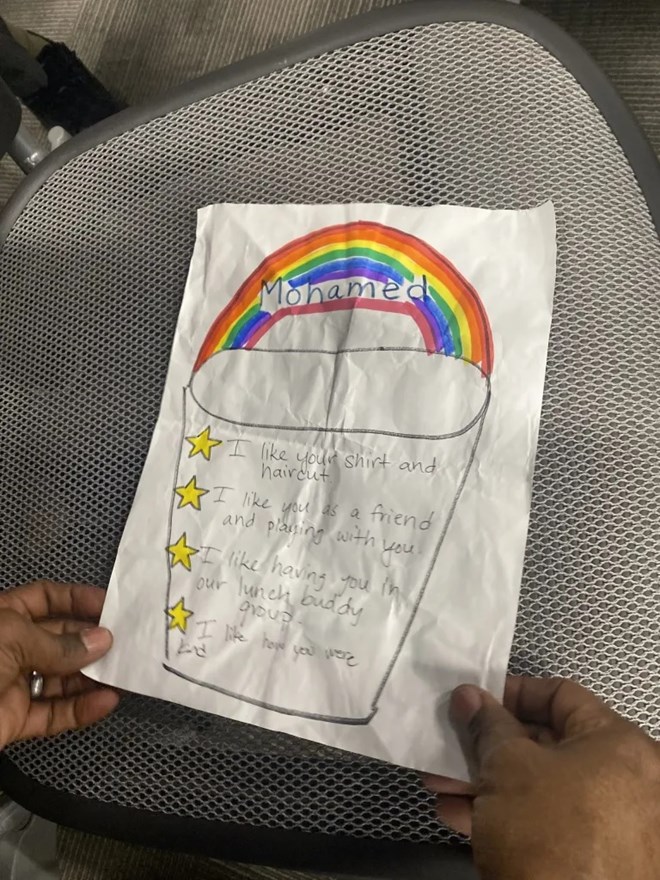

A presentation by a mother whose children attend school in a neighboring community illustrated how passions spread on the issue. She said her son had come home from school with a worksheet where a boy of the same sex was assigned to share what he liked about him. The paper listed the positive qualities of her son—“I like your shirt and haircut” and “I like you as a friend and playing with you.” Her son’s name is prominently written at the top in the middle of a rainbow drawn in marker. She also pointed out that the handwriting was that of an adult and questioned why the teacher had brought about this assignment.

A mother shows a worksheet with a rainbow that her son, who does not attend Burnsville schools, brought back from school. Credit: Abdi Mohamed | Sahan Journal

In the eyes of some parents, the worksheet meant that not only were schools teaching Somali students to accept LGBTQ individuals, but also that it would be okay for their children to be part of the LGBTQ community.

Her comments stirred the crowd, even as she clarified that her children do not attend Burnsville schools. Several of the parents rushed to look at the paper and snap photos on their phones. Some social media commentators wrote that the compliments, combined with the rainbow, provided evidence that first-grade boys were being taught to flirt with each other. One TikTok video amassed thousands of views. And the rainbow and first-grade compliments took on a life of their own online, fueling another round of social-media fears.

‘We’re talking in circles and we’re losing the moral of the story here’

One parent noted that Somali students are academically behind their peers, and disproportionately placed in special education and English language learning classes. Why, she questioned, would students learn about being allies to the LGBTQ community when they are failing in school? “I want my child to learn reading, writing, math,” she said. “If it’s not that, I don’t want that.”

One mother, whose children do not attend Burnsville schools, shared a worksheet her first-grade son had received in school. His name was in a rainbow, and other little boys had given compliments to each other. Parents concluded that teachers were instructing first-grade boys to flirt with each other. The image went viral on social media. Credit: Abdi Mohamed | Sahan Journal

One mother, whose children do not attend Burnsville schools, shared a worksheet her first-grade son had received in school. His name was in a rainbow, and other little boys had given compliments to each other. Parents concluded that teachers were instructing first-grade boys to flirt with each other. The image went viral on social media. Credit: Abdi Mohamed | Sahan Journal

But Somali district staff turned those academic concerns back on parents. The cultural liaisons said they had spent months trying to reach parents, only to have their calls go to voicemail. They regularly reach out to discuss issues related to cultural inclusivity and grades, they said.

Amal Osman is the cultural liaison at Burnsville High School and has been working with students and parents for the past two years. She describes her role as working to eliminate gaps between the school and parents, working on student achievement, and solving conflicts in a manner that is culturally respected. Amal believes that there are multiple factors that have contributed to the frustrations and concerns that have come to the surface in recent days.

“What we’re lacking is our kids’ understanding of who they are. They’re living in dual cultures,” she said. Amal believes that there’s a gap in communication between children and their parents brought on by the nature of living in an immigrant and refugee community. “Our community comes from a survival mode. My oldest is turning 13 on Thursday. She’s advanced, I can’t keep up with her,” Amal said. “Families have no fault in this. They just need to know that there are platforms and people that look like us who are willing to collaborate.”

Amal was encouraged by the turnout Monday, and implored parents to reach out to her and her colleagues. She regarded their attendance on Monday night as a testament to their love for their children, and not as a reflection of animosity towards another group of people. If a meeting date doesn’t work for a parent’s schedule, Amal stated that her door is always open.

Shamso Moalim is a cultural liaison for the district’s elementary schools and is a parent with three children in the district. Her perspective on the turnout was less optimistic.

“I don’t think a quarter of them will come back,” Shamso said. “This will be where they stop. Some came to record and take photos to show that they were here, but if there was a goal for them in this they would have come with accurate information and more direct questions. We’re talking in circles and we’re losing the moral of the story here.”

Several of the parents lingered after the meeting to plan their next steps. Attendees said they want to hear a clearer message from parents, and that they should be on the same page if they are to make requests of the school district.

Shamso said parents venting on Monday without correct information actually set the conversation back.

“We’re arguing over stuff we have no knowledge about,” Shamso told Sahan Journal. “It’s important for you to research the topic at hand before coming into a meeting like this, otherwise it’s embarrassing. You don’t want to spread misinformation around in the community and stoke more problems. All of this talk of a pill and a shot for gender therapy was spread by people in our community who mixed different pieces of news together.”

Maryan, who often attends the Somali parent meetings, said parents need to be more involved, not just when there is a controversial issue. “I’ve attended parent meetings in the past for other topics, but I’ve always stayed quiet and observed,” she said. “We have to get together and meet not only when we have issues with things, but to ask questions and be present. We’re here arguing over something that was put into law in 2013.”

Shamso and Amal said more should be done to educate families on how policies come about in the first place, and how change happens.

“People in this country are still fighting for rights based on skin color and women aren’t receiving equal pay for equal work, yet we think we can demand laws be changed overnight,” Shamso said.

Bellmont invited parents to attend their child’s school to sit in on their lessons, so they would know what their children were learning in school. Meanwhile, parents passed around a notebook to share contact information so they could stay in touch about future meetings. The list of names grew longer and longer.